The Politics of Race, Place, and Waste in Huntington Beach

N.B. The Historic Wintersburg Conservancy, a non-profit organization, prepared a nomination of the Wintersburg Historic District to the National Register of Historic Places. In November 2025, the California State Historic Resources Commission recommended Wintersburg (colloquially known as Historic Wintersburg) to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Because the property owner, Republic Services of Phoenix, Arizona, objected to listing, the National Park Service cannot formally list the property on the National Register but it can - and is expected to - determine it to be eligible. In any case, because of the unanimous decision of the State Historic Resources Commission, Wintersburg is now listed on the California Register of Historical Resources!!

By Jason Foo

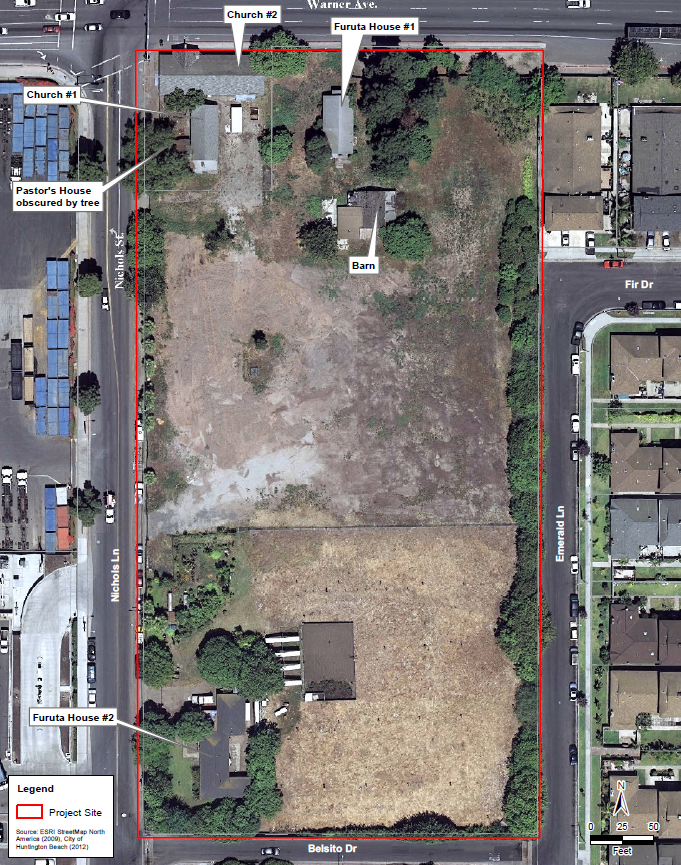

On most days people drive or walk past the boarded-up, crumbling white stucco building with the rainbow “Jesus Saves” mural without looking twice. The church on the southeast corner of Warner Avenue and Nichols Lane in North Huntington Beach is visible from the street, while the rest of the 4.4-acre site is hidden by chain link fence wrapped in privacy netting and overgrown trees. But on the morning of February 25 around 9 a.m., passersby could not help but notice smoke billowing above the property as a building became engulfed in flames. A few hours after the fire had been extinguished, two of the oldest structures were in rubble spread across the ground. This devastating turn of events brought attention to the little-known history of this corner – once a center of Japanese American life in early Orange County, it burgeoned at the turn of the twentieth century even before the now dilapidated building was dedicated in 1934 as the Japanese Presbyterian Church (figs. 1-3).

Today, the site known as Historic Wintersburg is part of Oak View, a predominantly Latino neighborhood. It is near a 17.6-acre waste transfer station owned by Republic Services, an $11-billion national waste disposal company and the landowner of the property. The stream of blue garbage trucks roaring past the church serves as a constant reminder of the long and contentious battle among various stakeholders – preservationists, Republic, the city of Huntington Beach, the Ocean View School District, Oak View residents, and the broader Japanese American community – for the future of a place over a hundred years old that even after fire and years of indifference and neglect retains its integrity and provides a rare picture of the lives of one of the city’s settler communities.

Fig. 3 Japanese Presbyterian Church, A.D. 1934. Jason Foo, Nov. 2021.

Japanese Pioneers in Early Orange County

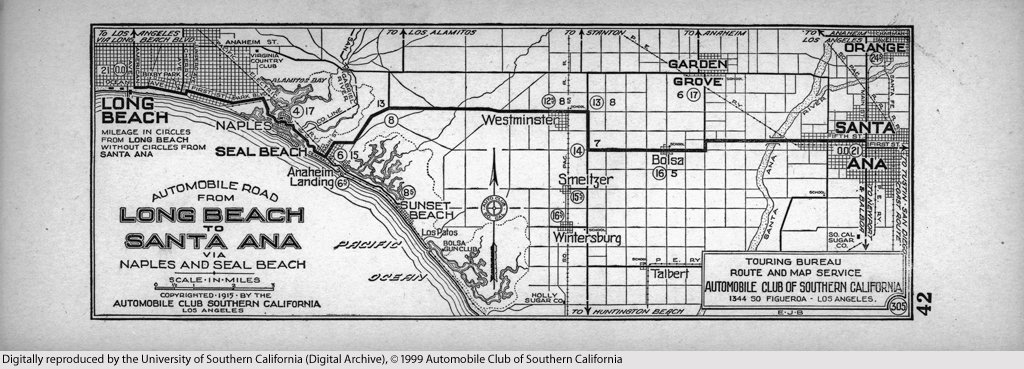

The four remaining structures on two contiguous, largely open-space parcels represent one of the last vestiges of Wintersburg Village, a farming community whose history dates to the late nineteenth century.[1] It predates the 1904 founding of Huntington Beach as a township and its 1909 incorporation as a city. The village remained unincorporated until 1957 when it was annexed by the city.

Historic Wintersburg is the former homestead of the Furuta family. At eighteen years old, Charles Mitsuji Furuta (1882-1957) left rural Hiroshima-ken for the US, part of a wave of Japanese migration to meet the demand for low-wage labor after Chinese immigration was restricted by the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. He arrived in Washington State in 1900. By the time he made his way south to the coastal peatlands named for farmer and landowner Luther Henry Winters, hundreds of Japanese workers could be found harvesting celery at makeshift labor camps in Northwest Orange County.[2] Japantowns grew around Christian churches and Buddhist temples, language schools, markets, and athletic clubs in the rural county, providing community for the first-generation Japanese American immigrant, or Issei, laborers (fig. 4).

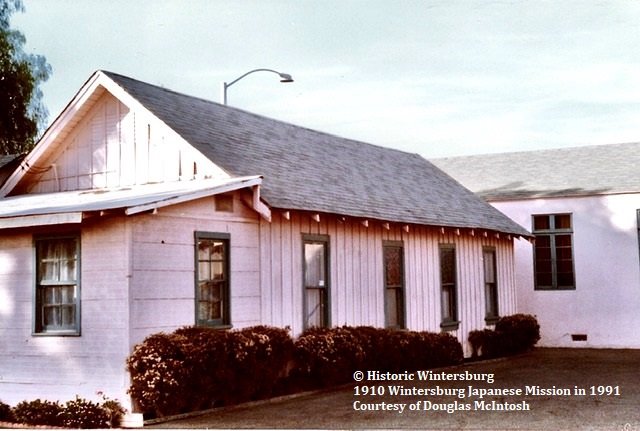

When the Presbyterian Church became interested in establishing missions in Japanese communities on the West Coast, Reverend Hisakichi Terasawa was dispatched from San Francisco to minister to workers in the celery fields. In 1904, he founded the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, Orange County’s first Japanese church. Furuta was one of its earliest congregants and the first Japanese to be baptized Christian in the county. The congregation met in a barn before Terasawa, with Furuta’s assistance, purchased five acres off Wintersburg Road (now Warner Avenue) in 1908 to build permanent structures. A twenty-five-seat chapel and a manse, or parsonage, to house clergy was completed in 1910 with donations from the community, which included local European Americans.[3][4] Two years later, Furuta acquired the parcel from Terasawa that would become his farm and home with wife, Yukiko Yajima (1895-1989), and their six children. He maintained the northwest corner for the mission and became one of its largest benefactors (fig. 5).

When the tide of anti-Asian sentiment swelled again, California responded by passing the Alien Land Law of 1913, the first of two laws preventing “aliens ineligible for citizenship” (which included Asian immigrants) from owning or leasing agricultural land.[5] Alien land laws were passed in more than a dozen other states, while the US government had imposed restrictions on Japanese labor migration in the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907-1908. The California laws targeted Japanese who had been successful in securing farmland and were considered competitors. As such, Historic Wintersburg is the rare Issei-owned land acquired before 1913.

Building and Rebuilding

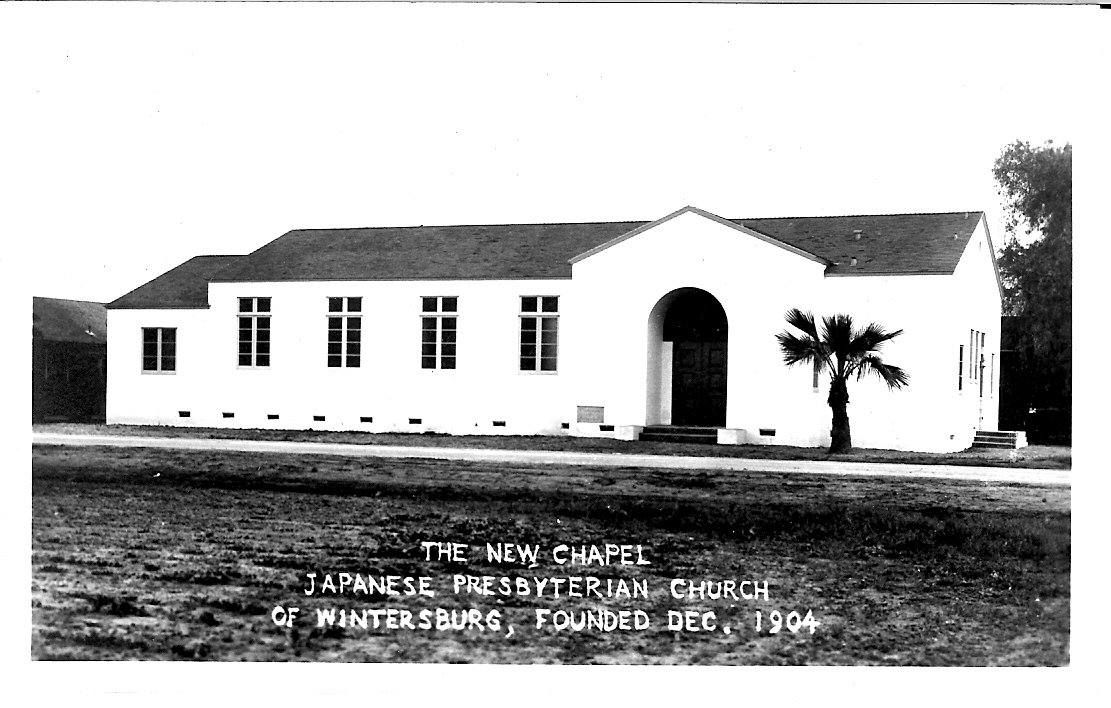

Furuta proved to be an enterprising landowner, first using his property to farm goldfish and later flowers. Begun in the 1920s, the C.M. Furuta Gold Fish Farm was the first business of its kind in Orange County. Its success spurred the establishment of two other Japanese-owned goldfish farms in Wintersburg, including one by his brother-in-law, Henry Kiyomi Akiyama, which became the largest goldfish hatchery in the West.[6] Furuta continued to give to the mission, donating more of his land for a larger building to accommodate its growing congregation (figs. 6 and 7).

The Japanese Presbyterian Church – a modest Spanish Colonial Revival building – was completed in 1934 in the midst of the Great Depression to serve an area with 150 Japanese families. With the exception of the war years, it remained in use until 1965 when the congregation moved to its present location in Santa Ana and became the Wintersburg Presbyterian Church. The building was leased to other congregations from 1968 to 1997, including the Rainbow Christian Fellowship and most recently a Hispanic congregation. It has since been in a derelict state with minimal security, inviting transients and vandals onto the property (figs. 8 and 9).

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Furuta and other prominent Japanese residents were arrested by the FBI. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Five-hundred-and-seventy-five Japanese Americans in the area were required to register in downtown Huntington Beach prior to their removal. Furuta was first imprisoned at Tuna Canyon Detention Station in Tujunga and then at Lordsburg Internment Camp in New Mexico before reuniting with his family and the rest of the Wintersburg community at the Poston Relocation Center in Arizona.

When the war ended, the Furutas returned to an overgrown farm and dry, silt-filled goldfish ponds. Charles and his son, Raymond, repurposed the ponds to grow water lilies, starting with the roots that had survived the war years (fig. 10). The rest of the land was used to grow sweet pea flowers. During the second half of the twentieth century, the farm was known as the largest commercial provider of cut water lilies in the country. Operations ceased in 1995, but the property remained with the family until 2004 when it was sold to Rainbow Environmental Services for a reported $4.6 million.[7] The employee-owned company was acquired by Republic in 2014 in a controversial sale, which led to a class action lawsuit against Rainbow.[8]

“A Minor Structure” Is Lost

Once threatened with demolition and long in need of maintenance to prevent hazards and further deterioration, Historic Wintersburg has been in a politicized and tenuous position for over a decade with preservation interests and land use regulations at odds with property rights and political influence. The extant structures include a pioneer barn (c. 1908-1912), the Furuta family homes – the 1912 earthen-red bungalow and Raymond and his wife Martha’s 1947 ranch house – and the Japanese Presbyterian Church. As with much of the land, remnants of the fish ponds are covered by dead grass, dry brush, and weeds (figs. 11-15). On February 10, two weeks before the fire, landowner Republic and the city were notified in writing of ongoing concerns about trespassing and the lack of maintenance and security when the front door of the church was found vandalized.

The fire destroyed the manse and severely damaged the original chapel – both founding mission buildings from 1910. The blaze started in the manse before spreading to the adjacent chapel, which was separated by a three-foot breezeway. The fire department made the request for Republic to use an excavator to tear down the damaged portions of the buildings and spread the debris due to the potential for structure collapse and to suppress embers that posed a threat to the 1934 church. Unfortunately, “an unintentional collapse of both structures occurred,” according to the fire investigation report. It noted that during the blaze fire crew believed the two structures were one L-shaped building. But even after attempts were made to provide accurate information, officials and Republic continued to refer to the loss of one structure and to claim the church had been saved when in fact one of the two churches were destroyed. In a post-fire statement, Republic referred to the mission complex as “a minor structure.” (figs. 16-22).

The exact cause of the fire could not be determined, but personal belongings were found amid the remains indicating a person was living on the premises, and live electrical wire was running across Nichols Lane to the burned buildings. The report revealed that a transient man, who was known to be camping on the property, was spotted in the area and heard yelling about a fire just before 9 a.m. by an Oak View resident. The only deterrence to trespassing onto Historic Wintersburg was the chain link fence in which police found large openings at the time of the fire. No charges have been filed and the fire has been deemed an accident.

Another Kind of Removal

Even with the mission complex gone, Historic Wintersburg remains a singular site representing Orange County’s early agricultural history, the last trace of one of Huntington Beach’s pioneer communities, the growth of the county’s Japanese Christian community, and three generations of Japanese American history. “It has this collection of buildings that really tells the arc of history over a century: the arrival, the settlement of Japanese Americans in California, World War II incarceration, and then the return after [the war], and the recovery of their lives,” according to Wintersburg advocate and historian Mary Adams Urashima. As preservationists have noted, most places that have been saved are related to World War II confinement. “There are very few sites like this that represent the daily life of Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans,” she told the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 2014.

Kenneth Hayashida, an advocate and member of the Wintersburg Presbyterian Church since 1994, believes the long and rich history of the congregation, which remains largely Asian American, is a significant reason to preserve its founding site. “The people in the congregation in the first half of the twentieth century were committed to faith [and] committed to country.” Perhaps the most famous congregant was James Kanno, Fountain Valley’s first mayor and the first Japanese American mayor in the continental US. “Given the history of racial tensions that developed as a result of World War II, the site is certainly unique,” Hayashida says, referring to the wartime survival of the Japanese Presbyterian Church. The building belonged to the local Presbytery, thus avoiding the confiscation that befell many Japanese-owned properties.

Resettlement after the war was difficult for Japanese Americans who faced displacement and bigotry. Most did not have property to return to, including the majority of Japanese on the West Coast and in Orange County who were involved in agriculture. Urashima is concerned with the continued removal of the Japanese American presence that began with the war. “Due to the fallout of World War II, a lot of the history of Japanese Americans in Orange County was essentially erased…through the urbanization of Orange County, the rezoning of farm properties – erasure which continues to happen.” Wintersburg Village was absorbed by Huntington Beach in one of several large farmland annexations between 1957 and 1960 around the time of the 405 Freeway construction through the city.[9][10] As it increased in size from 3.57 square miles to over twenty-five, the city began to rezone agricultural land for commercial, industrial, and residential uses to accommodate its fast-growing population.[11] If not decimated by wartime removal, many Japanese American communities were displaced by urban renewal.[12] “There was an effort in some places to remove [Japanese American sites],” according to Urashima. “Some were vandalized, some were burned down and lost forever. Some [land] got rezoned so in effect their use could not continue.” Amid the city’s own rapid expansion and urbanization, the Furuta farm became one of the last pieces of pre-war Japanese-owned land and is the only pre-Alien Land Law Japanese parcel in the city.

When Urashima began her research in 2004, she could find no reference to Japanese American history in Huntington Beach historical files.[13] In 2012, she started the Historic Wintersburg blog to address the gap in the historical record and to underscore its significance when it was threatened with demolition. “I thought the one thing I could do is start putting faces on these buildings, start personalizing the place, start telling the stories and the history of the place, help people understand the significant history it’s tied to.” Huntington Beach maintains an inventory of historic properties, but it lacks a preservation ordinance to designate and protect them as well as to administer consistent application of policy. As a result, an alarming number of resources have been lost to alteration or demolition.[14]

June Aochi Berk of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition stresses the importance of saving places associated with Issei history. “These places are valuable in the sense of keeping the story alive, of the first generation who came here and struggled to build a community in California.” As Legacy Project Director for the TCDS Coalition, Berk interviews descendants of Issei men who were imprisoned at the Tujunga center. She learned about one such prisoner, Charles Furuta, by interviewing his grandchildren, Norman and Ken Furuta. Berk, a Nisei, or second-generation Japanese American, was incarcerated as a child. She compares the threat to Issei-related sites to another kind of removal. “That’s what makes me want to preserve these places – to honor our first generation Isseis.”

A Contested Site

The relationship between Historic Wintersburg’s stakeholders is fractured after years of negotiations, litigation, accusations, and online harassment. When Urashima became aware of then-owner Rainbow’s intent to demolish all six structures in 2011, she sounded the alarm. In response to Urashima’s concerns, the Huntington Beach city council created through unanimous vote the ad hoc Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force to raise funds to purchase the property or to relocate the structures, and Urashima was appointed chairperson.

Individual buildings at Historic Wintersburg or the entire property have been recognized as historic resources of both local and national significance by multiple agencies and the city of Huntington Beach since the 1970s.

In a 1974 report prepared for the open space/conservation element of the general plan, the 1934 Japanese Presbyterian Church was identified on a list of twenty-one city landmarks.[15]

The Orange County Japanese American Council published a Historic Building Survey in 1986 listing thirty-three extant pre-1940s buildings. The list included the 1934 church, the original two-building mission complex, and the 1912 Furuta house. The 1910 chapel and manse were identified as the oldest surviving Japanese American religious structures in the county.

The chapel and the Furuta bungalow were included on a list of city landmarks in 1991 with an indication that they qualified for the National Register of Historic Places. The list was updated in a 2008-2012 historic resources survey by Galvin Preservation Associates to include all six structures as part of the 2015 update of the historic and cultural resources element of the general plan.

In August 2013, the National Park Service found in a preliminary evaluation that the “property retains a remarkable amount of integrity” and is likely eligible for listing on the National Register, reaching the same conclusion as previous reports.[16]

Preserve Orange County believes the site may be eligible for listing on the National Register based on all four criteria of significance: its association with events that have contributed to important patterns in the agricultural and social history of Huntington Beach and Orange County; its association with leaders of the Japanese immigrant and Japanese American community in Orange County; its embodiment of rural vernacular building types dating from the early- to mid-twentieth century; and its potential for pre-historical significance.

The land nearby Historic Wintersburg, where the waste transfer station is located, was first used for farming before it became a commercial and industrial area. According to building permits, Rainbow Disposal began operating in the mid-1960s. The company expanded its operations on Nichols over the years by acquiring adjacent parcels. Oak View Elementary School opened in 1967 across the street, followed by Oak View Preschool in 2001. It was not until 1981 when Rainbow began operating a solid waste processing facility at its current location.[17] It purchased the Wintersburg property in 2004 to prevent residential development and to maintain a buffer between incompatible land uses.[18]

Phoenix-based Republic, which acquired Rainbow for $112 million, operates in forty-one states and serves a number of cities throughout Orange County, including Santa Ana, Anaheim, and Irvine. It has an “evergreen” clause in its contract with Huntington Beach that renews automatically and stipulates a fifteen-year notice to terminate. The city council initiated a review of the contract in 2017 followed by multiple attempts to negotiate new terms on the agreement that began with Rainbow in 2006.[19] In 2019, the city council voted to cancel the contract in favor of a competitive bidding process, but the city remains bound to the terms until 2037.

In 2011, in a proposal known as the Warner-Nichols Project, then-owner Rainbow sought to rezone the medium-density residential land into commercial on Warner (1.1 acres) and industrial on residential Belsito Drive (3.3 acres) across from Oak View Preschool’s outdoor recreation area. The company also stated that the on-site rehabilitation of structures at Historic Wintersburg was infeasible due to cost and time and pursued action to demolish them. But without a plan for new development as part of its proposal, officials questioned the purpose of rezoning if the result would be fenced-off vacant land (fig. 23).[20]

The 2012 draft environmental impact report (DEIR) for the Warner-Nichols Project prepared by ICF International with the city as the lead agency was considered flawed by state and local experts. Preservationists criticized the report for inadequate historical analysis, separating each of the six structures for individual evaluation after previous reports established them as a collection of buildings potentially eligible as a historic district; for pursuing the demolition of an irreplaceable resource without an immediate need to do so; and for inadequate mitigation measures and alternatives to demolition for a project that went against the city’s own preservation goals as outlined in its general plan, among other reasons. For the Ocean View School District (OVSD) and Oak View residents, the DEIR failed to address the impacts of industrial development on its schools and nearby medium- and medium-high-density residential areas (fig. 24).[21]

Nonetheless, in November 2013 the city council voted 4-3 to certify the final environmental impact report and approve demolition. Then-Mayor Connie Boardman criticized the decision. “Right now, weighing the benefits of demolition and the benefits of bare land versus retaining these historic buildings, I can’t find reasons to support it,” she told The Orange County Register. “There’s no other property like it in Huntington Beach or Orange County.” The city council and Rainbow agreed to give the task force eighteen months to raise funds for the relocation of the structures.[22] The National Trust for Historic Preservation responded by naming Historic Wintersburg to its annual list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places in 2014. The next year, it was designated Orange County’s first National Treasure, indicating the National Trust was taking an active role in its preservation. Preserve Orange County added it to its own list of Most Endangered Historic Places in 2017.

A Right of Way

Less than one square mile in size, Oak View is among the most densely populated and lowest income neighborhoods in Huntington Beach. Along with the Japanese, Mexican farmers began leasing land in the area in the early twentieth century. The number of Mexican workers continued to grow in the county and across the state until they became the majority of agricultural labor in the 1930s. By the 1980s, Oak View had become a Mexican American enclave.

In response to the Warner-Nichols Project, Oscar Rodriguez, who grew up in Oak View, co-founded the grassroots group Oak View ComUNIDAD with Victor Valladares. With homes as close as 500 feet to the transfer station, residents smelled trash throughout the day and heard concrete crushing at night, while Oak View students contended with outdoor areas covered with dust and bird feces. “They had an uncovered facility for over thirty years that caused so much damage.”[23] Rodriguez, who is a Huntington Beach planning commissioner, says there was minimal pushback from residents over the years due to a language barrier and lack of advocacy on their behalf in a neighborhood he describes as “segregated” from the rest of the city. Gina Clayton-Tarvin, president of the Ocean View School District Board of Trustees and a trustee since 2012, says Republic was allowed to operate at the expense of Oak View residents, many of whom are undocumented, for years because “they don’t have a vote, so they don’t have a voice.” She is adamant when she says, “Nobody at the City of Huntington Beach gave a crap.” As witnesses to the effects of a fixed source of pollution on a marginalized community, Oak View ComUNIDAD and the OVSD became the voices of opposition to “environmental racism.”

Following the approval of the EIR, the OVSD filed separate lawsuits against the city and Rainbow on behalf of the Oak View schools. It claimed the city had violated the California Environmental Quality Act in certifying the report, while it initiated legal action against Rainbow for the noise and odor impacts of its twenty-four-hour operations on students as well as on the neighborhood’s residents. In June 2015, the Orange County Superior Court ruled in favor of the district and ordered the city to reverse the zoning change, a decision new owners Republic said it supported.[24] In November 2016, the parties reached terms on a settlement in which the company agreed to enclose its facilities and install filtration and ventilation systems at a cost of $18 million and to pay up to $4 million for the construction of a gymnasium at Oak View Elementary.

As part of the terms, Republic entered into a restrictive covenant with the OVSD whereby the company cannot expand its operations onto Historic Wintersburg; rezoning of the parcel must be approved by the district; and the land may never be used for housing. Since the streets surrounding Oak View Preschool – Nichols, Belsito, and Emerald Lane – fall within the OVSD’s boundaries, new owners would need to obtain an easement to use the streets, further encumbering the property. For its part, the district supports saving Historic Wintersburg, recognizing its value as a cultural and educational resource.

More Than a Home

The settlement paved the way for a restart of negotiations in 2017. When Republic indicated it was open to selling the property for preservation, the task force and national partners, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Trust for Public Land, began talks with the company to purchase the site for fair market value. But in January 2018, Republic gave notice it intended to sell the land to Public Storage, stunning many who believed the parties were working toward a mutually agreeable solution. In response, the Historic Resources Board, an advisory board to the Huntington Beach city council, Japanese American organizations, and Preserve Orange County reiterated their support for Historic Wintersburg. Permanent restrictions on the property (which made self-storage units one of the few viable development options), coupled with criticism of the proposed sale, may have been too much for the potential buyer to overcome, and a deal never came to fruition. By April 2019, Republic had ceased communication with the task force and its partners. The next month, the city council dissolved the task force “by virtue of time, change in composition, and goals” when it had become “an independent group of citizens,” and removed all references to it from the city’s website.[25]

Critics of the task force, who were vocal in their opposition, had raised concerns about its role in a private property dispute, referring to it as a “land grab” that was unfair to its owners after the Furutas had profited in the sale. Other detractors have casted doubt on the site’s significance.[26] Norman Furuta, the son of Raymond and Martha who grew up on the farm, has acknowledged it was through Urashima’s advocacy that he began to understand the importance of the property. “For me and for members of my family, the structures in question were just a place that my family called home or went to church, not something that we considered historically significant and certainly not something that might be of interest to the community at large,” he told The Rafu Shimpo in 2014 when the National Trust added Historic Wintersburg to its most endangered list.

It is not surprising that Furuta would not recognize his family’s home as historic given the difficulty Urashima had in finding information on local Japanese American history. Rodriguez, who would walk past the former Furuta farm on his way to Ocean View High School, says he never learned about Wintersburg in school and was unaware of its history until he became involved in community advocacy. In recent years, preservationists have been reexamining the criteria by which landmark designation is conferred to address the lack of diversity on historic registers. The emphasis on historical significance and physical integrity in determining what is worthy of preservation has marginalized places with less widely-known histories and vernacular building types often associated with minority groups.

A Path Forward

Despite setbacks and a years-long online harassment campaign trafficking in racial tropes directed at Urashima and Japanese Americans and attempting to devalue the importance of the site, Urashima and her allies have persisted in their advocacy. In November 2020, the Historic Wintersburg community group engaged the nonprofit Heritage Museum of Orange County in a formal partnership to receive donations for the purchase of the property. Preserve Orange County, which has supported the site’s preservation since the organization placed it on its Most Endangered list, became an active partner earlier this year to work toward securing the future of the site.

The newly-formed coalition sees the Heritage Museum, a Santa Ana-based history center which includes a collection of late nineteenth-century buildings, gardens, and citrus groves on twelve acres, as a programmatic and stewardship model. According to Jamie Hiber, the museum’s executive director, saving Historic Wintersburg is in line with its mission to preserve the heritage of Orange County. “If we’re given this opportunity to be more proactive in our mission work, we have to do this.” Referring to civil rights history and the legacy of Japanese American incarceration, Hiber says, “We need spaces like this to celebrate resilience, to talk about difficult things. Our primary focus is to provide a platform for these stories to be shared.” The coalition’s hope is to engage in substantive talks with Republic to sell the land it continues to pay property tax on.

Restoration of the aging structures and maintenance of the property will be costly and a long-term commitment. But as one of Huntington Beach’s few remaining open spaces of its size in an underserved, food-insecure area with several schools nearby, it is not difficult to imagine its potential as a historic site with a museum, park, urban farm, and other community-serving uses (fig. 25). For Republic, given the legal encumbrances on the property, selling it to be developed into a heritage park and green buffer between Oak View and its operations may be the only sensible path forward. For now, it sits vacant and the remaining structures continue to be susceptible to more hazards.

The loss of two 112-year-old buildings has underscored Historic Wintersburg’s vulnerability and strengthened the collective resolve to see it saved. A few weeks after the fire on March 19, a rally in front of the Japanese Presbyterian Church organized by the Progressive Asian Network for Action brought out over a hundred supporters, including Asian American activists, OVSD trustees, and local residents, demanding action and answers (figs. 26 and 27). Yet despite statements of support from officials in the fire’s aftermath, sustaining political will and satisfying stakeholders are considerable hurdles.

With the displacement or demolition of most prewar Japanese American communities, it is imperative to save what remains. Historic Wintersburg has survived nearly unchanged for over a century despite anti-immigrant and anti-Asian land laws, wartime incarceration, and postwar urbanization that paved over much of Orange County’s Japanese American landscape. As the last vestige of one of Huntington Beach’s pioneer communities and a lesser-known but integral part of the region’s history, it is the most significant Japanese American historic site in the county. At a time when greater representation of places that tell diverse histories is needed and an obvious candidate for preservation is at risk, the path forward is clear.

ENDNOTES

[1] The Warner Avenue Baptist Church at 7360 Warner Avenue, founded as the Wintersburg M.E. Church in 1906, predates Historic Wintersburg as the oldest remaining structure from Wintersburg Village.

[2] Japanese in Wintersburg became successful farmers of beans, chili peppers, and sugar beets after a blight began destroying celery crops around 1905.

[3] I refer to the mission building as a chapel as per the Orange County Japanese American Council Historic Building Survey and to distinguish it from the two-building mission complex, of which it was a part, and the 1934 Japanese Presbyterian Church. The mission received formal recognition from the Presbyterian Church in 1930.

[4] The first residents of the manse were Reverend Kenichi Inazawa and his wife, missionary Kate Alice Goodman, whose interracial marriage was illegal in California.

[5] Japanese immigrants were able to evade the law by purchasing land in their US-born children’s names until the Alien Land Law of 1920 was revised in 1923 to restrict the rights of their children to possess land.

[6] Akiyama later established the Pacific Goldfish Farm on forty acres in present-day Westminster, which was advertised as the largest in the West. See Mary F. Adams Urashima, Historic Wintersburg in Huntington Beach (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014), 89-92, 169.

[7] As reported by Anthony Clark Carpio, “Commission Turns Down Wintersburg Site Owner’s Plans,” Daily Pilot, August 21, 2013, https://www.latimes.com/socal/daily-pilot/news/tn-dpt-xpm-2013-08-21-tn-hbi-me-0822-wintersburg-20130821-story.html; Josie Huang, “OC history: Japanese-American Site Makes ‘Most Endangered’ List, KPCC, July 18, 2014, https://archive.kpcc.org/blogs/multiamerican/2014/07/18/17025/oc-japanese-american-most-endangered-wintersburg/.

[8] In 2017, 400-plus current and former employees of Rainbow filed a legal complaint challenging the sale of the company’s employee stock ownership plan assets to Republic in violation of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. In June 2021, Republic agreed to settle the class action lawsuit for $7.9 million.

[9] Thirtieth Street Architects, Inc., Historic Resources Survey Report: City of Huntington Beach, PDF file, 1986, https://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/files/users/planning/1986-Historic-Building-Survey.pdf, 5.

[10] The city annexed eleven farmlands between 1957 and 1960. See ICF International, Warner-Nichols Draft Environmental Report, PDF file, 2012, https://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/government/departments/planning/environmental-reports/files/Draft-Environmental-Impact-Report--Warner-Nichols.pdf, 3.1-2.

[11] The population of Huntington Beach grew from 11,492 in 1960 to 112,021 in 1969. See Galvin Preservation Associates, City of Huntington Beach Historic Context & Survey, PDF file, 2014, https://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/files/users/planning/Historic_Context_and_Survey_Report_Final_Draft.pdf, 34.

[12] Page & Turnbull, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in California, 1850-1970 Multiple Property Submission, PDF file, 2020, https://ohp.parks.ca.gov/pages/1054/files/CA_MultipleCounties_AsianAmericans-and-PacificIslanders-in-California%20MPS_MPDF_SLR.pdf, 39-42.

[13] Arthur A. Hansen, Professor Emeritus of History and Asian American Studies at Cal State Fullerton, founded the Japanese American Oral History Project at CSUF in 1972, and was co-director of the Honorable Stephen K. Tamura Orange County Japanese American Oral History Project established in 1981. Both projects collected a number of interviews with prominent Japanese Americans in Orange County, including Yukiko Furuta and brother-in-law Henry Kiyomi Akiyama.

[14] Since the 1986 historic survey of the downtown area, more than half of the city’s historic resources have been destroyed. See City of Huntington Beach Historic and Cultural Resources Element, PDF file, 2015, https://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/files/users/planning/Historic-And-Cultural-Resource-Element-with-Matrix-2018.pdf, 22.

[15] Thirtieth Street Architects, Inc., Historic Resources Survey Report: City of Huntington Beach, 46-47.

[16] Tim Gregory, Historic Resources Technical Report: The Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission/Church and the Furuta Residences, PDF file, 2002, https://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/files/users/planning/Appendix_C.pdf, 10.

[17] Environ Strategy Consultants, Inc, Phase I Environmental Site Assessment, PDF file, 2004, https://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/files/users/planning/Attachment_11_Phase_I_ESA.pdf, 6-10.

[18] In 2002, an application was submitted to the city to develop fifty-three condominiums on the land but was later withdrawn due to its proximity to the industrial site.

[19] Erik Peterson and Lyn Semeta, City of Huntington Beach, Notice of Termination of Rainbow/Republic Services Evergreen Contract, File 19-409, April 1, 2019, https://records.huntingtonbeachca.gov/WebLink/DocView.aspx?id=5322825&dbid=0&repo=COHB&cr=1.

[20] Anthony Clark Carpio, “Future of Historic Site Still in Question,” Daily Pilot, April 24, 2013, https://www.latimes.com/socal/daily-pilot/news/tn-dpt-xpm-2013-04-24-tn-hbi-0425-wintersburg-20130424-story.html.

[21] ICF International, Warner-Nichols Final Environmental Impact Report, PDF file, 2013, https://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/government/departments/planning/environmental-reports/files/Environmental-Impact-Report-Final-&-Response-to-Comments--Warner-Nichols.pdf.

[22] According to Urashima, the task force has never asked the city for funds to preserve or relocate the structures.

[23] At the time Rainbow constructed its facilities, the state did not require enclosures around waste transfer stations.

[24] “Since Rainbow ES was acquired by Republic after 2013, Republic determined that it no longer sought to use this property for the purposes that were intended leading up to the certification and rezoning in 2013,” said City Attorney Michael Gates. See Greg Mellen, “Ocean View Continues Lawsuit over Garbage Dump Site Next to School in Huntington Beach,” The Orange County Register, June 3, 2015, https://www.ocregister.com/2015/06/03/ocean-view-continues-lawsuit-over-garbage-dump-site-next-to-school-in-huntington-beach/.

[25] Ursula Luna-Reynosa, City of Huntington Beach, Dissolution of the Ad Hoc Wintersburg Committee, File 19-530, May 6, 2019, https://records.huntingtonbeachca.gov/WebLink/DocView.aspx?id=5349998&dbid=0&repo=COHB&cr=1.

[26] Chris Epting, “City of Huntington Beach Quietly Erases All Mentions of the Wintersburg Task Force,” Surf City Chronicles (blog), April 3, 2019.